Self Improvement vs Self Acceptance

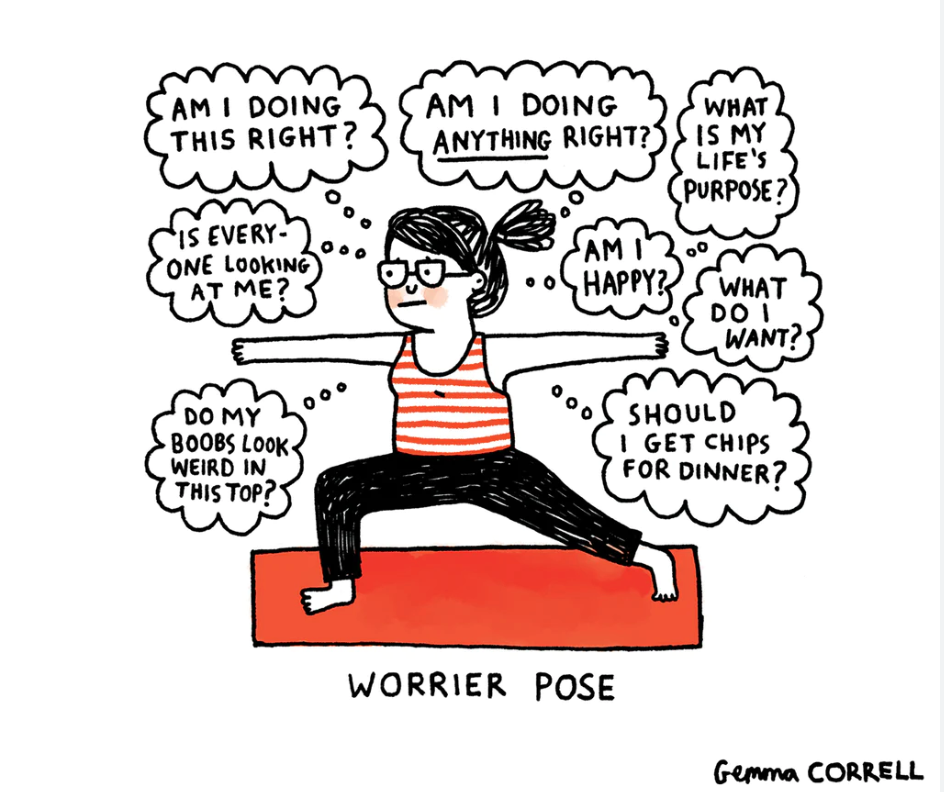

My inner critic is a real bitch.

I call her The Trunchbull (à la Roald Dahl’s Matilda, pre-censorship).

Since childhood, her hard-ass voice has helped me become a general high-achiever type. But it’s also left the emotional debris of crippling perfectionism in its wake. It’s taken a decade of deep reflective work to relax the inner Trunchbull and learn to be a little more forgiving with myself.

Shout out to all the other recovering perfectionists out there.

Why do we do this? Here are 2 reasons:

1. Humans have an evolutionary need to belong.

As social creatures, we naturally place a hefty emphasis on what other people think. Story checks out. As infants, we needed our caregivers’ love to survive, yet we never really unlearn that hard-wired drive to pursue approval.

The inner critic is a judgemental voice in our heads, pointing out all the ways we fall short or could do better. It is trying to protect us from losing love. It wants to make sure we’re perceived as valuable, therefore included, and therefore safe.

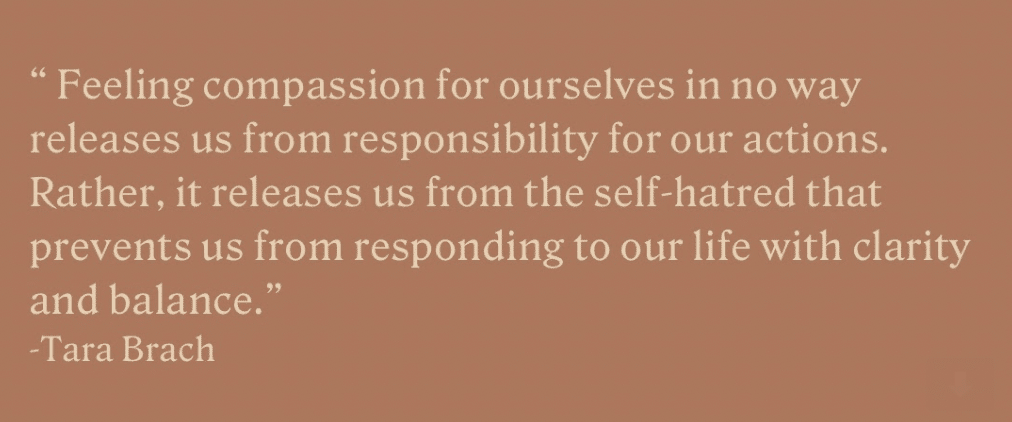

The problem is when our inner critic gets out of control. It starts telling us lies, saying awful things that aren’t even true, on repeat, until we’re caught in a whirlpool of shame and low self-esteem. Tara Brach calls this ‘the trance of unworthiness’. This often unconscious spiral of criticism can affect how we make choices, how we are with others, and lead to a subtle sense of not feeling at home in ourselves.

2. Our psyches soak up the stories of our culture.

Humans are incredibly porous to collective narratives. The story of consumer capitalism is one of not-enoughness, of scarcity. I’m talking about how we live in a framework that feeds on a need for us to believe our worthiness can be purchased in a $200 tube of skincare / hotter bikini / bigger house / 6 week online course that guarantees freedom from self-doubt for good!

The internalisation of this narrative is symptomised by an unconscious itch that we should be doing more, getting more, and being more. There’s a special kind of existential dread triggered by an empty Sunday spent at home without ‘achieving’ anything ‘productive’.

Introducing a new story of enoughness, allows us to decouple our sense of value and worth from our ability to generate capital. To relax what Bob Sharples calls the “subtle aggression of self improvement”.

Perfectionists Anonymous.

The first step is admitting you have a problem. If I were to run P.A. meetings (new class at H.K perhaps?) the second step would be recognising when striving for constant betterment is being driven by an underlying assumption of inherent not-enoughness.

Through this lens, perfectionists live in constant fear of failure. As if revealing our human flaws will result in the rejection of all who love us and banishment from society.

Are you a (recovering) perfectionist? If you’re reading this and criticising your ability to be less critical, or feel like you’re failing at accepting yourself, then maybe yes.

The irony is, idealising a perfected version of ourselves is what gets in the way of meaningful change. It prevents us meeting our ‘self’ as we are.

Like the beautiful Sarah Powers always said, perfection will only be found by a willingness to accept the imperfect.

I often hear self-acceptance confused with complacency.

This is missing the mark. Acceptance, as an attitude, doesn’t have to exclude engagement in what matters to us.

Let’s talk about the concept of compassion.

Buddhist psychology aligns the heart-quality of compassion with the ability to take skillful action in the face of suffering. Its ally is insight, as we first need to see ourselves and situations clearly, without getting entangled in them. This trains our capacity to face what is difficult, rather than turn away. The culmination of true compassion includes the courage to engage with pain in a way that is helpful.

Self-compassion, truly caring for ourselves, includes a willingness to turn towards all the difficult facets of our humanness, then take actions that genuinely support our long-term wellbeing.

Sometimes people mistake self-compassion as weakness. Au contraire. Like Brianna Wiest says, true self-care isn’t all about face masks and salt baths. It might not even look pretty. Think of doing the hard work to break unhelpful behaviour patterns, or resisting the urge to keep playing the victim in our own lives. That stuff ain’t always insta-feed worthy.

This yang aspect of care can be called ‘fierce compassion’.

Fierce compassion comes from a place of love, rather than lack.

There are yin and yang aspects within all things. Sometimes big tenderness is required at first. This is why insight is so important; gaining discernment to know the nature of our own suffering, before we choose the most skilful response.

In the Brahma Viharas practice (training the awakened heart), we learn to spot the near and far enemies of compassion. An obvious far enemy (the opposite) is cruelty. However, a near enemy is pity. It’s close, but not the same. Identifying these near enemies can navigate us through misplaced expressions of care, and orient back towards what is truly helpful.

For example, when fierce self-compassion goes too far it can become grasping and greedy. Or when tender self-compassion becomes too passive it can slippery dip into the soggy self-pity of victimhood.

I made us a cheat sheet:

Kristin Neff is a leading researcher on self-compassion. She defines it as,

Treating yourself with the same kindness, concern, and support you’d show a dear friend.

The past decade has seen an avalanche of scientific studies into self-compassion. Findings include links to:

- Reduced anxiety, depression, stress, shame and disordered eating.

- Increased life satisfaction, confidence, body-appreciation and immune function.

- Improved resilience in the face of trauma, chronic health, or parenting challenges.

- More caring and supportive relationship behaviour.

- Greater motivation, less fear of failure, and more personal responsibility.

How does it work?

If/when your inner Trunchbull says things like “you idiot”, “you look terrible”, “you’ve really gone and f*cked that up now haven’t you” it activates the threat system of the brain.

When we are self-critical, we become both the attacker and the attacked. Our physiology responds with fear. As the stress response turns inward, our sympathetic nervous system tries to either fight (more self-judgement), flee (self-isolation or shame), freeze (overwhelming rumination or self-absorption) or fawn (this one wasn’t in the research yet – perhaps the reflexive response is to appease the critical voice?)

Kristin Neff describes how self-compassion counteracts these responses.

When we are internally kind to ourselves, it activates the neurophysiology of care.

Imagine hearing the voice of a powerful inner friend and ally, rather than an inner enemy. This ‘tend and befriend’ response soothes our nervous system and helps us emotionally regulate. It generates feelings of safety in response to threats.

The way we are with ourselves moves in rhythms.

Like all of life. The kind of compassion we need will fluctuate through the seasons of our days, our decades. The fierce flows from the tender. The ability to be with suffering is a delicate balancing of grit and grace.

And of course it is more than two-sided. As we accept the complexity of the human experience we find that we are each a constellation of stories that birth our ways of being with ourselves and each other.

Cultivating both acceptance AND openness to change is the path to a wise response.

We practice this on our yoga mat: abhyāsa-vairāgya-ābhyāṁ tan-nirodhaḥ. The blending of dedication and surrender. To never give up and always let go. Both. Together.

This work is the doorway to boundless compassion (karuṇā), a heart that is vast enough to hold all of life in its circle of care. Because we go way past our edges. And it’s easier to feel this when we finally lift what Ani Pema calls ‘the ancient burden of self-importance’.

This is what we mean by our 4th core value at Human.Kind, ‘We hold space for the chaos and the beauty within ourselves, and the world.’ It’s the most any of us can do.

And probably nobody will ever get it right. But as Jack Kornfield always says, the point was never to perfect ourselves, but to perfect our love.

Yours in kindness,

Tessa

More info / resources:

– I studied this extensively with Tara Brach. Her book ‘Radical Compassion’ is a good place to start.

– Excellent research paper by Paul Gilbert (2020) from tradition to science: Compassion: From Its Evolution to a Psychotherapy

– An article by Kristin Neff from the Greater Good Science Centre at UC Berkeley: Why Self-Compassion Trumps Self-Esteem

– Brené Brown interviewing the brilliant compassion researcher Chris Germer in her podcast, re: the near and far enemies of compassion in social justice.

– Our MBSR course (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) with Clinical Psychologist Rene Martin-Harris. Excellent entry to insight and compassion practices in an accessible, secular style.

– Sharon Salzberg’s book Real Change is EPIC. She’s a leading U.S. insight meditation teacher.

– I recorded a short talk and guided meditation for compassion this week. Free for members via the On Demand section of our App.